Who was the first star of the Grand Ole Opry? If asked, most people would think for a minute, then mistakenly name such country greats as Jimmie Rogers, Uncle Dave Macon, or maybe even Roy Acuff. Contrary to popular belief, however, the Opry’s first performer and, arguably, its first star, was none other than DeFord Bailey, an African-American performer born and raised in Tennessee.

Originally known as the WSM Barn Dance, the Grand Ole Opry was given its name by popular radio announcer George D. Hay in 1927. Nashville’s WSM radio had just become part of the fledgling NBC Radio Network and, in response to a network broadcast of conductor Walter Damrosch’s “Musical Appreciation Hour,” Hay quipped, “friends, the program which just came to a close was devoted to the classics. Doctor Damrosch told us that it was generally agreed that there is no place in the classics for realism. However, from here on out, for the next three hours, we will present nothing but realism. It will be down to earth for the ‘earthy’.”

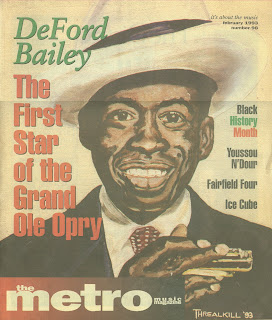

DeFord Bailey: The First Star of the Grand Ole Opry

Hay then introduced one of the Barn Dance’s most frequent and popular performers, a man he dubbed the “Harmonica Wizard,” DeFord Bailey, who performed his classic train song, “Pan American Blues.” After Bailey’s typically spirited performance, Hay mouthed the phrase that would become music history: “For the past hour we have been listening to music largely from Grand Opera, but from now on, we will present ‘The Grand Ole Opry’.” The legendary Opry and Bailey, its first star, were born.

Bailey’s road to the Opry was a difficult one. Born in 1900 in rural Smith County, Tennessee, about 40 miles east of Nashville, Bailey was the grandson of a freed slave who had fought for the Union Army during the Civil War. DeFord’s mother died when he was only a year old; his father’s sister, Barbara Lou, and her husband, effectively became his foster parents, caring for him throughout the rest of his childhood.

As a boy, DeFord grew up among a musical family, a passion he passed on to his own children and grandchildren, who are also musicians. His son, DeFord the Second, a multi-instrumentalist himself says, “it ran through the family.” DeFord learned the traditional tunes of what he would later call “black hillbilly music” from his grandfather, aunt and other family members. He learned to play the mouth harp while a child and it remained his favorite instrument. DeFord was a multi-talented musician, however, able to play a banjo, guitar, mandolin, and even a bit of violin. During DeFord’s teens, the Bailey family would often perform together at church gatherings and barn dances.

DeFord had toyed with the idea of actually making a living performing the music he loved so much; in 1925 he received his first big break. Radio had come to Nashville in the form of station WDAD, owned by a radio supply storeowner named L.N. Smith. The store – called “Dad’s” – was managed by Fred “Pop” Exum, a radio enthusiast and a fan of DeFord’s who quickly asked Bailey to perform on the air. Though the station was small by any standards, broadcasting at a mere 150 watts, its signal reached out hundreds of miles through the night air, drawing fan mail from such far-flung locales as Atlanta, Philadelphia, and New York.

Nashville’s WSM radio, owned by regional economic powerhouse National Life and Accident Insurance, went on the air a month later. It was here that Hay, lured to the station from WLS in Chicago, began the Saturday night show of authentic folk and country music that would become the “Barn Dance.” The line-up of musicians would often include many WDAD regulars, who would play at both stations on Saturday nights.

WSM Barn Dance

One of these regulars, Dr. Humphrey Bate, a respected country doctor and well-known musician, talked DeFord into joining him up on the hill at WSM one night. Arriving while the show was already in progress, Bate told Hay that he wanted DeFord to play on the air. It was only with Bate’s insistence that Hay begrudgingly agreed to allow DeFord to play a couple of tunes. After Bailey’s performance, though, Hay was elated at the young man’s talents and added him as a regular to the show. DeFord appeared as a weekly regular, bringing in large quantities of fan mail, as well as telegrams and phone calls with special song requests.

As an Opry performer, DeFord helped to carry the show during its early years, offering an excellent balance to other performers such as Uncle Dave Macon and the McGee Brothers. Bailey’s popularity led the enthusiastic Hay to believe him ready for the stardom proffered a recording artist and chose him as one of the three Opry acts to be recorded by Columbia Records in an Atlanta session in early 1927.

These sessions proved to be ill advised and unproductive, leading Hay to cancel the deal and instead contract with the Brunswick label to record Bailey in New York. The two New York sessions would yield eight songs, including the classic “Pan American Blues.” The songs were released in 1927 as part of Brunswick’s Songs From Dixie series – the only recordings by a black performer among the series. They were also issued by Vocalion, Brunswick’s sister label, and several were also reissued in 1930, again by Brunswick.

Though evidence exists to support the contention that the records were commercial hits, DeFord saw little in the way of royalties (an occurrence not uncommon with black performers to this day). As David C. Morton relates in his excellent biography of Bailey, DeFord Bailey: A Black Star In Early Country Music, DeFord was supposed to receive $400 cash for the recordings, as well as 2% royalties on each record sold. George Hay took 25% of the cash payment for arranging the sessions, paying out the remaining $300 in weekly increments of $10 (which also supplanted the $7 he was paid weekly for his Opry performances). Bailey also received three royalty checks totaling $128 for the songs, less than half, by any estimates, than he should have been paid.

A year later, Hay had set up the first recording session to ever take place in what would later become the “Music City,” luring the Victor label (later RCA) to town to record his Opry performers. DeFord took part in this historic session, cutting eight new songs in four and a half-hours. Three of these songs would later be released by Victor, the last, “John Henry,” was released in 1932. Reissues of the material were released as late as 1936.

Although DeFord saw little gain from these recordings – his entire catalogue of commercial releases weighing in at just eleven songs – their influence on a generation of harp players can still be felt today. No other harmonica player during those early days of recording and radio was captured so well onto vinyl; Bailey’s success led to a rash of field recordings of other Black harmonica soloists and paved the way for popular artists such as Sonny Boy Williamson. After the disappointing pay-off of recording (DeFord received a lump sum of $200 for the Victor sides), Bailey never really tried to record again after 1928.

Unhappy with the money he was receiving from WSM, and with George Hay, Bailey was lured to Knoxville by W.C. “Pay Cash” Taylor to appear on WNOX radio (for $20 a night, nearly three times what Hay was paying him!). Bailey’s debut performance was a smash success, running two hours past the scheduled ending time and prompting dozens of long distance calls to the station from satisfied listeners. His regular appearances drew fan mail from several states to the small station. DeFord soon began to itch for something else, though, even considering a trip to California to try his luck there. Convinced by Taylor and Hay into returning to Nashville, Bailey, after insisting on the same money he was making in Knoxville, rejoined the Opry in 1929.

Roy Acuff & Bill Monroe

During the 1930s, Bailey toured constantly with several bands, playing tent shows, county fairs, and theaters across the country, always returning to the Opry stage for Saturday night’s performance. Being a black man in a white man’s world presented many problems as segregation forced DeFord to find other places to eat and sleep than his fellow performers. The old shibboleth of money also raised its head again, as the five dollars a day DeFord received for performing barely paid his travel expenses and was often significantly less than that which his fellow (white) performers were paid. Often times Bailey was cheated in the amount paid him, or offered whiskey as payment (which Bailey, a teetotaler, politely refused). His was the star that attracted crowds out to the shows during the depression as people paid fifty cents apiece to see DeFord and the other Opry performers in person.

During the 1930s, Bailey toured constantly with several bands, playing tent shows, county fairs, and theaters across the country, always returning to the Opry stage for Saturday night’s performance. Being a black man in a white man’s world presented many problems as segregation forced DeFord to find other places to eat and sleep than his fellow performers. The old shibboleth of money also raised its head again, as the five dollars a day DeFord received for performing barely paid his travel expenses and was often significantly less than that which his fellow (white) performers were paid. Often times Bailey was cheated in the amount paid him, or offered whiskey as payment (which Bailey, a teetotaler, politely refused). His was the star that attracted crowds out to the shows during the depression as people paid fifty cents apiece to see DeFord and the other Opry performers in person.By the late ‘30s, DeFord had befriended a young fiddler from East Tennessee by the name of Roy Acuff. Acuff came to the Opry in 1938 as an unknown; realizing the popularity of the harp player, he asked DeFord to tour with his band. DeFord did so, helping publicize Acuff’s “Smoky Mountain Boys” with his drawing power over the next couple of years, directly lending a hand to Acuff’s future stardom. Bill Monroe, the King of Bluegrass music, also utilized Bailey’s talents and drawing power on tour to publicize his band.

The spring of 1941 saw Bailey start his sixteenth year with the Grand Ole Opry and its radio broadcast. Even though his airtime had been cut back, he still appeared as frequently as any other artist, including thirty weeks during 1939, and remained one of the show’s most popular performers. Within a couple of months, though, in May of 1941, Bailey was fired by the Opry, a mystery often covered up or neglected by country music historians. Although authors through the years have come up with many theories or facts, claiming racial reasons or, as the official party line stated, the fact that DeFord wouldn’t learn any new songs, the truth behind his dismissal probably lies somewhere in betwixt the two.

According to George Hay, the Opry’s founder and guiding light through the early years, as written in his account of the Opry, “like some members of his race and other races, DeFord was lazy. He knew about a dozen numbers, which he put on the air and recorded for a major company, but he refused to learn any more, even though his reward was great…” Bailey biographer David C. Morton believes that Bailey was merely caught up in an industry-wide boycott of songs administered by the ASCAP licensing agency. Prohibited for legal reasons from performing many of his best-known songs on the air, DeFord lost his value to the Opry. After leaving the Opry, Bailey opened a shoe shine stand in downtown Nashville that he worked until his death in 1982.

Actually, DeFord knew dozens of traditional songs that he had grown up playing and had written many more. Of his refusal to learn any new songs, his son DeFord the Second says, “that part I know is wrong. The songs that I know today that he taught to me, he learned to play different after I had grown up.” According to most accounts, DeFord had the soul of a jazz artist, often improvising on the spot, with each performance being slightly different and equally special.

Country Music Hall of Fame

Bailey’s role as the Opry’s first performer and an important factor in the show’s future success, as well as his role as country music’s first African-American star, has been sadly overlooked by the Nashville establishment. To this day Bailey remains an obscurity, a footnote in the history that he helped create. Even at the Opry, his status has been forgotten, as observes DeFord the Second, “all these stars have gold and bronze framed pictures on the wall, Dad’s picture is nowhere to be seen.” In 2001, the Academy of Country Music got a lot of press out of the nomination of Charlie Pride as the first African-American member of the Country Music Hall of Fame. Bailey remains the only founding member of the Grand Ole Opry refused this great honor.

Although racism has certainly played a part in denying this musical pioneer his place in the Country Music Hall of Fame, and thus a permanent place in musical history, many industry insiders dismiss Bailey as an insignificant artist. The simple fact however, is that black or white, people loved DeFord Bailey. He was a musician of considerable talent, depth and charisma, drawing large audiences with his live performances and creating a legion of dedicated fans with nearly two decades of radio appearances – people who cared not of color, but came to hear the music that DeFord Bailey loved playing so well.

[Note: The story of DeFord Bailey was brought to me by my late musician friend Aashid Himons, who was a friend of the Bailey family and an outspoken advocate for the artist’s induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame. Nothing happened for better than a decade after our article on DeFord was first published in 1993 by Nashville’s The Metro magazine. Reprinted by my friends at Big O magazine in Singapore the early 2000s, however, the article caught the eye of country music fans in Australia, who reportedly deluged the institution with letters asking why Bailey wasn’t a member, often accompanied by copies of this article. Curiously, Bailey was subsequently inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2005.]

Buy the book from Amazon.com: David C. Morton's DeFord Bailey: A Black Star In Early Country Music

No comments:

Post a Comment