Wayne Kramer is a bona fide rock ‘n’ roll legend. As guitarist for

Detroit’s MC5, Kramer was part of an anarchic, creative band that was a

major inspiration for both the late ‘70s punk revolution and the early ‘90s

alternative rock movement. Kramer’s four late ‘90s solo albums recorded for

the independent Epitaph label with members of bands like Bad Religion, The

Melvins, and Claw Hammer only added to his already considerable musical

legacy.

The guitarist also recorded albums with Johnny Thunders

(Gang War), British rock legend Mick Farren (Death Tongue), Brian James of the Damned (Mad About the Racket), and former MC5 manager John Sinclair (Full

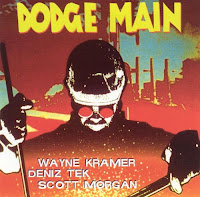

Circle), among others. Perhaps the most exciting album that Kramer recorded aside

from the MC5 was the 1996 Dodge Main

album, a sort of Motor City “homecoming” with Kramer, Deniz Tek of Radio

Birdman, and Scott Morgan of the Rationals and Sonic’s Rendezvous Band.

Kramer

passed away this week at the age of 75 after a brief fight with pancreatic

cancer. This phone interview was published in 1997 in my R Squared music zine.

It has become somewhat of a cliché,

but in practice, Wayne Kramer is usually referred to as a “legend.” It would

be much more accurate, perhaps, to label him as a survivor. As guitarist for

Detroit’s notorious and influential MC5 – musical mouthpiece for the

revolutionary White Panther Party – Kramer made it through the tumultuous ‘60s

alive, if not unscathed. He’s lived through poverty, drugs, and prison to

emerge from the other end of despair. Picking up the guitar again during the

‘80s for a series of musical collaborations with folks like Johnny Thunders

and Mick Farren, it wasn’t until Kramer’s mid-‘90s emergence as a significant

solo artist that he’d begun to forge his own identity and earn the critical

respect he’s always deserved.

“For me, I didn’t really have a

choice,” Kramer says of his chosen career path, “this is what I have to do.

I’ve been confused about a great many things in my life, but I’ve never been

confused about my reason to exist. It’s always been to do this work, to play

this music. In the end, to hopefully share something with other people like

they have shared with me...the things that I’ve gotten from great music, from

great art. That sense that maybe I’m not alone, maybe I can spread that idea

to someone else, that maybe they’re not alone, hopefully to leave the place a

little nicer than I found it.”

As one of the few icons of the ‘60s still standing, what are Kramer’s memories of the era? “They were exciting and romantic, but they were dangerous. You never knew when something bad was going to happen. You never knew what direction it was going to come from. If it wasn’t the police, it was the right wing – the ‘America, love it or leave it,’ John Birch Society – you add to that mix the volatile passions of the day, the militant rhetoric, and the fact that most everybody was high on acid most of the time, it was a time that was unique. That’s one of the things that I tried to do with Citizen Wayne, to try and grab a snapshot of what it was like. Songs like “Down On the Ground” or “Back When Dogs Could Talk,” that sense of limitless possibilities, that we could change the world, that there could be a new kind of politics, a new kind of music.”

The Motor City seems a strange place to grow musical legends like the MC5 or Iggy and the Stooges. What was it about Detroit that allowed for this kind of musical phenomena? “I think it was that there were jobs there,” says Kramer. “There was work, and there was kind of a boomtown atmosphere, a sense that we could do anything in Detroit. If you wanted it built, manufactured, fabricated, we could do it in Detroit. People worked hard for their money and they wanted their bands to work hard. We carried that work ethic to the band and in the kind of music that we liked. It was what we called ‘high energy’ music. It was a visceral music, it was not a pretty, delicate music; it was a hard music. It was the music of James Brown, the avant-garde free jazz movement, Chuck Berry, and the rhythm section at Motown. Later, it was the music of the Who and the Yardbirds, that was experimental and pushed things.”

In many of the songs on Citizen Wayne, as well as his previous solo work, Kramer treads on political ground that is anathema to rock artists these days. With a perspective every bit as radical today as it was in 1969, Kramer is not afraid to take an artistic stand. “The wage and wealth gap is the human rights issue of today,” he says. “We don’t have the war in Vietnam now; we don’t have the generation gap. What we have is the difference between wealthy people and all the rest of us. I don’t believe that any thinking person can be an optimist today. I do believe that we are prisoners of hope. One sign that I see as really hopeful is that the unions are coming back.”

After touring throughout 1997 to support Citizen Wayne, Kramer will begin work on writing the soundtrack album for a proposed movie version of Legs McNeil’s history of New York punk, Please Kill Me. Afterwards, Kramer’s future is wide open. “My plan is to do an album a year for the next ten years, do a tour every year,” he says. “Music is not the kind of thing that is tied to being young. It’s something that you can continue to do through your thirties, your forties, your fifties...and continue to do it with meaning and passion. For me, my plan is to ‘do the work.’ That’s what living is all about. Push this music and sound into a more pure sonic dimension and try to write some good songs, tell some of the stories of what it’s like to be alive in this time and this place.” Like the true survivor that he is, Kramer works to create something that will live on beyond his brief time here. “Ultimately,” he says, “maybe I can become a blip on the horizon of our day.”

Also on That Devil Music:

Wayne Kramer’s Citizen Wayne CD review

Wayne Kramer’s The Hard Stuff CD review

No comments:

Post a Comment