For those of you who have been living under a rock, People, Hell and Angels is a twelve-song collection of previously-unreleased Hendrix studio tracks, most of them from the pivotal year of 1969 when the Jimi Hendrix Experience broke up and the guitarist was wanting to explore new musical directions with fresh collaborators. Although most of these songs have been released in different forms, on both live and studio LPs, you’ve never heard ‘em quite like this, this high-flying dozen revealing new dimensions to Jimi’s talents as a musician, songwriter, and producer.

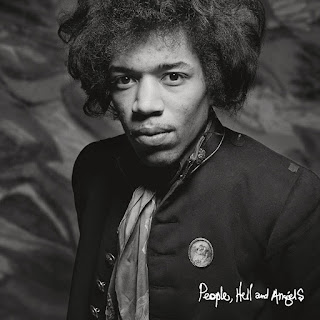

Jimi Hendrix’s People, Hell and Angels

The album-opening “Earth Blues” differs from the previous version released posthumously in 1971; the guitarist leading the power trio of bassist Billy Cox and drummer Buddy Miles (i.e. the “Band of Gypsies”) through their paces on a muscular, sparse hard rock construct. Built on Hendrix’s soulful vocals and laser-precise guitar licks, the rhythm section lays down the slightest of funk grooves to propel the song forwards. It’s not a great song, but it ain’t half-bad either, Hendrix’s fretwork displaying a fluid and natural feel, the lyric-heavy broth indicative of where the guitarist’s creative head was at this distinctive period in time.

Of much greater interest, personally, is the previously-undiscovered “Somewhere,” originally recorded in 1968 for Electric Ladyland. The take here was nearly lost to the ages, and features Stephen Stills laying down an awkward but intriguing bass line against Miles’ syncopated drumwork as Hendrix’s guitar soars unpredictably above the fray. “Somewhere” was previously heard on the widely-criticized Alan Douglas production Crash Landing, and Mitch Mitchell had overdubbed his percussion atop Miles’, but this version captures the song as originally envisioned, and while not a smash, it’s a healthy rocker nonetheless.

Hear My Train A Comin’

People, Hell and Angels mixes more than a little blues into the rockin’ funk that Jimi was delving into in 1969, beginning with a scorching take on “Hear My Train A Comin’,” derived from the first recording session with Cox and Miles. Influenced by innovative fretburners like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Albert King, this one is a real barn-burner. Jimi takes the blues into territory that only Stevie Ray Vaughan would later explore, his high-flying axe screaming tortured sounds and distorted blues licks above a beefy rhythm track. This unreleased take slows down the tempo, revs up the amperage, and blows out the speakers like nobody else before or since.

Ditto for “Bleeding Heart,” an inspired Elmore James cover culled from that same first session with Cox and Miles. Hendrix had evidently been messing with the arrangement for this personal favorite of his for some time, unhappy with previous attempts at capturing on tape what he felt in his heart, and this take, while maybe not nirvana to Jimi, certainly hits the modern listener’s sweet spot. Mid-paced with a solid groove, Hendrix rides Cox’s hearty bass line with reckless aplomb, embroidering James’ original sound with quickly-evolving guitar solos that seemingly change every few bars and provide enough fresh ideas to fuel an entire generation of future guitarists.

Izabella

Hendrix brought in his old friend, saxophonist Lonnie Youngblood, for the rockin’ R&B rave-up “Let Me Move You,” the pair backed by an unfamiliar band that included keyboardist John Winfield on this 1969 session outtake. It doesn’t really matter who’s backing Youngblood and Hendrix, however, the pair jetting into the stratosphere on a wildfire performance fueled by Winfield’s rapid keyboard riffs, Hendrix’s scattershot notes, and Youngblood’s raucous vocals and screaming sax. In the aftermath of the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, Hendrix took his then-current band, the informally-titled Gypsy Sun & Rainbows, into the studio to try and capture a keeper on his new tune “Izabella.”

The version of “Izabella” on the posthumous War Heroes sounds little like this one, which evinces a deeper rhythmic groove courtesy of bassist Cox and Experience drummer Mitch Mitchell and percussion courtesy Jerry Velez and Juma Sultan. Hendrix brings in a second guitarist, too, his old friend Larry Lee to add rhythm while Hendrix delivers his usual unbelievable solos above a dense, richer sound. Recorded the same night and, says the extensive liner notes provided People, Hell and Angels by Hendrix aficionado John McDermott, in-between takes of “Izabella,” the instrumental “Easy Blues” is a find. Longer and more fully-realized than the version found on 1981’s chop-shop creation Nine To the Universe, this take is allowed to flow more naturally, developing the interplay between Hendrix and Lee and the rhythm section, resulting in an electric and energetic performance.

Crash Landing

When producer Alan Douglas somehow grabbed the rights to the Hendrix tape library in 1974, he released a number of posthumous albums – Crash Landing, Midnight Lighting, and Nine To the Universe – that are now widely reviled by the hardcore faithful. Part of this had to do with Douglas’ misguided efforts to spotlight Jimi’s talent by stripping everything from the master tapes except for his guitar and vocals, and filling in with anonymous session musicians. This move proved to be stupid plus ten, because part of Jimi’s genius was the inspiration and energy he took from his musical collaborators, which is nowhere more apparent than on “Crash Landing.” Recorded in early 1969 with Cox and drummer Rocky Isaac of the Cherry People, Hendrix was trying to create something funkier, jazzier, and yet bluesier than previous with complex rhythmic patterns and imaginative guitar solos.

Although the band struggles to keep up, as shown by this previously-unreleased take, the musical ideas and experiments undertaken by the guitarist are simply breathtaking. Another example of this artistic vision can be found on “Mojo Man,” a song from brothers Albert and Arthur Allen, old friends of Jimi’s. Originally recorded by the brothers at the Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama in 1969, Hendrix asked them about the song in 1970 (when he had them singing back-up on “Dolly Dagger” and “Freedom” from Cry of Love). Working with a tape provided by Albert Allen, Hendrix pumps up the song with his finest funk licks ever, riding high in the mix alongside Allen’s soul-drenched vocals, an unnamed horn section blasting away, and New Orleans pianist James Booker’s nuanced accompaniment. The result is a lively, engaging slab o’ early 1970s R&B.

The Reverend’s Bottom Line

There’s much more, of course, to explore on People, Hell and Angels, and even the album-closing, unfinished jam “Villanova Junction Blues,” from that productive first session with Cox and Miles, provides hints and signs of the musical directions that Hendrix wanted to explore: bluesier, funkier, jazzier, but with the power and potential of hard rock. It’s hard to tell where Hendrix’s restless muse may have taken him during the decade of the 1970s when rock ‘n’ roll exploded into a myriad of styles (glam, metal, punk, progressive), but it’s a safe to say that the guitarist would have been at the forefront of whatever was fresh and exciting in popular music.

People, Hell and Angels is a superb collection, not merely another retread of the live performances we’ve heard from Jimi time and time again. This is the sort of stuff upon which Hendrix built his immense legacy, proving – better than 40 years after his death – that the praise is well-deserved. (Experience Hendrix/Legacy Recordings, released March 5th, 2013)

Buy the CD from Amazon: Jimi Hendrix’s People, Hell and Angels

No comments:

Post a Comment