When I was thirteen years old, there was a kid in my Erie, Pennsylvania neighborhood named Rick DiBello. Four to five years older than the rest of us, we got to know him because he dated the sister of one of our fellow juvie “gangstas.” A rocker-in-the-making, DiBello always had the best dope and was on the leading edge when it came to new music. So when he began ranting about a band called Spirit and their new album, Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus, we all sat up and listened.

DiBello was right – Spirit was the most righteous rockers these ears had ever heard. Guitarist Randy California (nee Wolfe) had learned his chops as a wee sprout sitting at the feet of the master, Jimi H. himself. As a teen, he played with blues greats like Sleepy John Estes and Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry. Spirit drummer Ed Cassidy, an imposing bald-headed percussion maniac, was California’s stepfather and had earned his props playing in big bands and jazz ensembles with folks like Zoot Sims and Dexter Gordon.

During the mid-‘60s, Cassidy played with Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal as part of the band Rising Sons; the band’s vocalist at the time, Jay Ferguson, went on to fame and fortune both as a solo artist and as frontman for Jo Jo Gunne. Bassist Mark Andes was to fly the coop along with Ferguson after Twelve Dreams to play with Jo Jo Gunne. Keyboardist John Locke had played with Cassidy in a jazz band. All of which is to say that Spirit had some solid musical credentials to do what they did.

What this odd combination of musical souls created in Spirit had never been heard before and has never been duplicated since. Mixing disparate elements of rock ‘n’ roll, classical, jazz, blues, folk, and psychedelic rock, Spirit could, at times, be spacey, focused, forceful, laid-back, structured, and improvisational, sometimes all at once. California took guitar playing to levels undreamed of even by Hendrix, layering subtle flourishes beneath the flowing instrumentation of some Spirit songs, directly punctuating other songs with razor-sharp directness. Cassidy and Andes comprised a solid rhythm section, which became the backbone of many songs while Ferguson’s and, to a lesser extent, California’s vocals were appropriate for the material, seldom bombastic and, most of the time, actually somewhat subdued.

I remember, years later, reading some critic’s comment that if Spirit had been a British band, their peak years (1968-1971) would have brought them a great deal of fame. As it was, they remain a critical favorite, an obscure footnote in rock ‘n’ roll history, although their musical output stands as some of the most innovative, daring, and exciting music ever made. Like many Spirit fans, I eagerly awaited the 1996 Sony Legacy reissues of the band’s first four albums. Many of us thought that this project – overseen by Randy California and offering 20-bit re-mastering, track notes, and bonus cuts – would serve to introduce the band to an entirely new generation of fans. Along with Cassidy, California had kept Spirit together through some lean years, and through recent indie releases and touring, had begun creating a buzz around the band again.

Unfortunately, with the Sony Legacy reissue project completed and scheduled for release, California tragically died in a fatal accident off the coast of Hawaii, his home for the past few years. Trying to save his son from an ocean undertow, California rescued the boy but was swept out to sea himself. Over a year later, I don’t recall reading that his body was recovered. In light of this tragedy, the reissues of Spirit’s first four albums became Randy’s legacy rather than a starting point for greater things. For music lovers, however, these four albums mark a watershed in rock ‘n’ roll, the point where musical virtuosity and stylistic differences fused together to make a single musical form that, although tagged as “rock music,” actually transcends the narrow limitations of that genre.

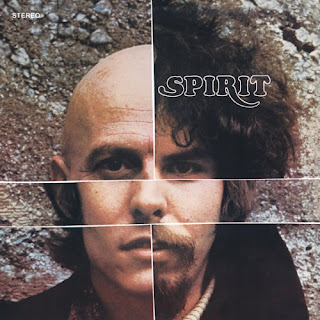

Spirit, the band’s self-titled debut, was originally released in 1968 and serves to set the stage for things to follow. The band created an instant buzz on the U.S. West Coast where, with bands like Buffalo Springfield and Canned Heat, they helped create a thriving rock scene in the scenic Topanga Canyon area. Sharing a house with Barry Hansen of “Dr. Demento” fame (considered the unofficial ‘sixth’ member of Spirit), the band began creating a musical imprint that was as unique as it was inventive. Several tracks from this first disc have become known as classics, notably “Fresh Garbage,” which would be covered live by Led Zeppelin, and “Mechanical World.” Listen to the opening of “Taurus” and you’ll know where Zeppelin later copped the melody for “Stairway To Heaven.”

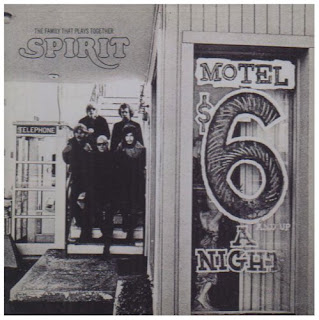

The Family That Plays Together, the title a bit of satirical wordplay on Cassidy and California’s father/son relationship, was released as Spirit’s sophomore effort a year later. Yielding a hit single and future “classic rock” radio staple in “I Got A Line On You,” the disc continued the inspired improvisational nature of the band, adding a little more rock ‘n’ roll edginess than their debut. The band’s fleeting brush with fame would make 1969 a heady year, with Spirit touring as headliners with opening acts like Led Zeppelin, Chicago, and Traffic before finally playing the Atlanta Pop Festival in front of 100,000 people. The Family That Plays Together holds some wonderful moments, songs like “Poor Richard” and “Silky Sam” or “Drunkard” sounding as vital and fresh today as they did almost 30 years ago.

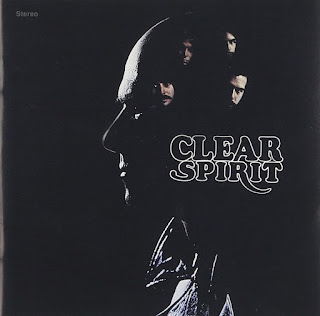

With the modicum of fame that they were enjoying, Spirit’s fortunes began to unravel. Released in late 1969, Clear shows a band under the gun, stressed by too much time on the road and unrealistic expectations. The tension is evident on Clear, the music displaying a harder edge that their previous works, rocking with abandon and more force than they’d shown before. A minor hit song emerged from the album, “1984” earning the band a loyal European audience even while the song was all but banned from airplay in the United States. The political turmoil of the country at large is evident on Clear, with cuts like “Policeman’s Ball,” “So Little Time To Fly,” and the aforementioned “1984” showcasing a newfound social awareness. In a perfect world, the album-opening “Dark Eyed Woman” would have been a huge hit. Instead, the band began its descent into obscurity and eventual break-up.

With a single stupid corporate decision that would seem to be in line with the American Indian’s sale of Manhattan to the white man for a handful of trinkets, the band’s label (Epic Records) decided to send Spirit on a radio promotional tour rather than have them play Woodstock. Offered a plum spot opening for former California mentor Jimi Hendrix, Spirit would certainly have emerged from the festival as superstars. Instead, fate would lead them to record their magnum opus, Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus. An inspired mix of every musical trick that spirit had in their considerable arsenal of skills, Twelve Dreams stands up, decades later, as one of the classic rock recordings of all time. Tracks like “Nature’s Way,” “Animal Zoo,” and “Mr. Skin” are masterful musical expressions. Mixing their improvisational backgrounds with a traditional three-and-a-half minute rock song structure, the band created music that was chaotic genius.

Released in 1970, Twelve Dreams would go on to become Spirit’s best-selling album and the one lone title in their catalog that has never been out-of-print. It would also become the original band’s swansong as well, Ferguson and Andes announcing – before the album’s release – their departure from the band to form the more pop-oriented Jo Jo Gunne. The original band broke up and a mediocre follow-up to Twelve Dreams titled Feedback was recorded without Randy California, who had suffered a head injury during a horse-riding accident. Released in 1971 under the Spirit name, it remains a deservedly lost chapter in the band’s history.

Brothers Al and John Staehely – recruited to replace the band’s departing members – led this less-than-stellar line-up, which also included Cassidy and Locke. When Cassidy left, he was replaced by a series of lesser drummers, including Cozy Powell, and the band toured in support of Feedback before officially breaking up altogether in 1973. In the meantime, California retreated to Hawaii for a couple years before he and Cassidy got back together to form a new version of Spirit in 1974. The band was subsequently signed to Mercury Records for a handful of albums, the best of which are represented by Spirit: The Mercury Years.

The two-CD set culls material from the band’s mid-‘70s efforts. Much of the original spark of the band was gone, however, although California managed some impressive guitar pyrotechnics and Cassidy remained a solid drummer. Bassist Barry Keane, who played on 1975’s Spirit of ’76 was a pale imitation of Mark Andes, and wasn’t used on the following year’s Son of Spirit album. With Jay Ferguson destined for solo stardom, Andes returned to the fold for 1976’s Farther Along, bringing his guitarist brother Mark with him from Jo Jo Gunne. John Locke also dropped back into the Spirit line-up for this album, probably the band’s best since Twelve Dreams. A year later, the conceptual Future Games – a Randy California solo album in reality – proved to be the band’s last for Mercury.

Although Spirit’s mid-‘70s releases never matched the innovation and execution of their first four albums, there’s still some good material documented by Spirit: The Mercury Years which has withstood the test of time. California’s ode to Jimi Hendrix, “Sunrise,” is a fitting tribute to the influential guitarist while covers of “Walkin’ The Dog,” “Like A Rolling Stone,” and “Hey Joe,” original taught to California by Jimi, offer new perspectives on those classic songs. The wonderful “Green Back Dollar,” inspired by the assassination of John Lennon, is included here as an unreleased bonus track. Among its whopping 47 songs, Spirit: The Mercury Years includes almost all of the double-album Spirit of ’76 set; nine of ten tracks from Son of Spirit; and eleven of twelve from Farther Along we well as other odds and ends.

For newly won fans of the band, Spirit: The Mercury Years offers most of Spirit’s middle-period albums on two discs without having to go out and dig up higher-priced vinyl copies of these rarities. The Esoteric Records label in the U.K. reissued Spirit’s first five albums in early 2018 as a five-disc set in clamshell packaging titled It Shall Be, which is a cost-effective way for buyers to grab them all up (even the dreadfully mediocre Feedback) at once though, to be honest, the band’s essential first four can be had on CD for a pittance.

Randy California kept Spirit alive until his death in 1997 with Ed Cassidy, then in his 70s, still pounding the skins with the energy and fervor of a man a third of his age. Musical soulmates, this duo proved to be the artistic and intellectual heart of Spirit. Driven to play, to create, and to perform, California was one of the greatest artists and most tragic figures in rock music. Although he lived well into his 40s, and saw a musical career that spanned better than three decades, California never received the level of respect and success that his work truly deserved.

Originally published in Review & Discussion of Rock ‘n’ Roll zine, 1998

Buy the CDs from Amazon.com:

Spirit

The Family That Plays Together

Clear

12 Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus

Spirit: The Mercury Years

It Shall Be: The Ode & Epic Years 1968-1972

No comments:

Post a Comment