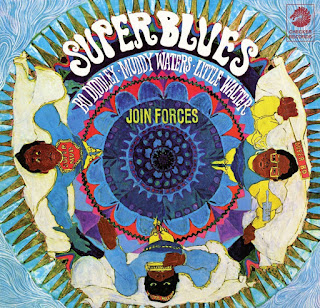

Although the label's experiments in electric blues, rock, and funk found varying levels of critical and commercial success, few of them prompted the debate garnered by 1967's Super Blues and the following year's The Super, Super Blues Band. The former featured the trio of Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, and Little Walter Jacobs performing in an informal studio jam session, while the latter album replaced the late Little Walter with the great Howlin' Wolf. Super Blues is the better of the two releases, although the second is criminally underrated, and while blues traditionalists have largely dismissed both albums, they served as an important gateway to the blues for many young fans at the time of their release.

Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters & Little Walter's Super Blues

The truth is, Super Blues is a heck of a lot of fun! Although harp legend Little Walter was hanging on by a thread during the recording sessions, the backing band – including guitarist Buddy Guy and longtime Waters' sideman Otis Spann on piano – picked up the slack. The spotlight deservedly shines on Diddley and Waters, the two talents sparring with each other in the studio while delivering solid performances. Super Blues opens with the low-slung Waters' track "Long Distance Call," the master's slide-guitar complimented by Walter's subtle harp while the vocals are nicely split between all three men; Little Walter's hoarse, underpowered voice is overshadowed by the bravado of his co-stars.

Diddley's "Who Do You Love" is provided a reckless, almost riotous performance as Bo and Muddy jawbone with each other above the song's familiar, reliable rhythm. The guitars scream and soar while drummer Frank Kirkland and bassist Sonny Wimberley hold down a fat bottom line. Waters' signature song "I'm A Man" – actually penned by Diddley – represents a duel for the ages, the two aging stars vying for top dog status on a tale that in and of itself is fueled by ego-driven braggadocio. As the song's notorious riff circles the studio like a raging tornado, Waters and Diddley deliver a heavyweight championship bout that could only end in a draw.

You Can't Judge A Book By The Cover

Chicago blues legend Willie Dixon – a talented musician, producer, and songwriter – was instrumental in the success of both Diddley and Waters, so it's only right that he is represented on Super Blues by three of his better songs. "You Can't Judge A Book By Its Cover" was Diddley's last chart hit back in 1962, and had subsequently been covered by blues-loving rockers like the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds. The version here is down and dirty, with unrelenting rhythms, a chaotic harp line, and chiming guitars dancing alongside Kirkland's machine-gun drumbeats. Waters' entry from the Dixon songbook, "I Just Want To Make Love To You," dates back to 1954 and represented one of the Chicago blues king's biggest hits. A bona fide blues standard, the song has also been successful in the hands of the Stones and, most notably, Foghat, although it's also been covered by Etta James, Chuck Berry, and Buddy Guy, among many others.

On Super Blues, "I Just Want To Make Love To You" is slowed to a smoldering, languid pace, the song's circular riff surrounding Waters' sultry vocals like a halo around his head, Walter spending the last of his strength blowing a fiery solo while Spann pounds the ivories like a madman. It's a strong performance, made all the more entertaining by the verbal jousting between Waters and Diddley. Little Walter takes the spotlight for a low-key replay of his 1955 Dixon-penned #1 hit "My Babe." The vocals are wisely shared by the three stars, as Walter's voice is barely heard in the mix, but it's an engaging performance nonetheless. The album closes with Diddley's spry "You Don't Love Me," Walter's jaunty harp paving the way for some imaginative fretwork on an electrified mix of blues and rock that was a good decade ahead of its time.

The Reverend's Bottom Line

Both Bo Diddley and Muddy Waters would experience ebbing fortunes in the wake of Super Blues and 1968's The Super, Super Blues Band. Although Diddley's commercial peak pre-dated the British invasion of the early-to-mid-1960s, his studio flirtations with funk and rock on albums like 1970's The Black Gladiator and 1972's Where It All Began failed to reignite his career, although they've since been reappraised as solid efforts. Hitting the rock 'n' roll oldies circuit, Diddley remained a popular live performer until his death in 2008.

By contrast, experiments like Waters' Electric Mud (1968) and After The Rain (1969), while doing little to breathe new life into the blues legend's then-moribund career, did lead to triumphs like 1969's Fathers and Sons album, recorded with Michael Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield, as well as The London Muddy Waters Sessions in 1972. These, in turn, led to Waters' late-career resurgence with a brace of albums produced by guitarist Johnny Winter, efforts like 1977's Hard Again and the following year's I'm Ready cementing Waters' already considerable legacy as the greatest the blues has to offer.

Super Blues is by no means a groundbreaking album, but it has withstood the test of time to become a minor classic in its own right, a raucous affair that's well worth another listen for Bo Diddley and Muddy Waters fans alike. Although this Get On Down Records 2013 reissue of Super Blues omits a pair of Little Walter songs from a previous 1992 CD reissue, considering Walter's health when they were recorded, listeners might be better off tracking down one of the esteemed bluesman's "greatest hits" albums for his timeless versions of the missing "Juke" and "Sad Hours." (Get On Down Records, released November 19, 2013)

Also on That Devil Music:

Muddy Waters' Electic Mud CD review

Bo Diddley's The Black Gladiator CD review